Data visualization rules, 1915

Right now people in data visualization tend to be interested in their field’s history, and people in digital humanities tend to be fascinated by data visualization. Doing some research in the National Archives in Washington this summer, I came across an early set of rules for graphic presentation by the Bureau of the Census from February 1915. Given those interests, I thought I’d put that list online.

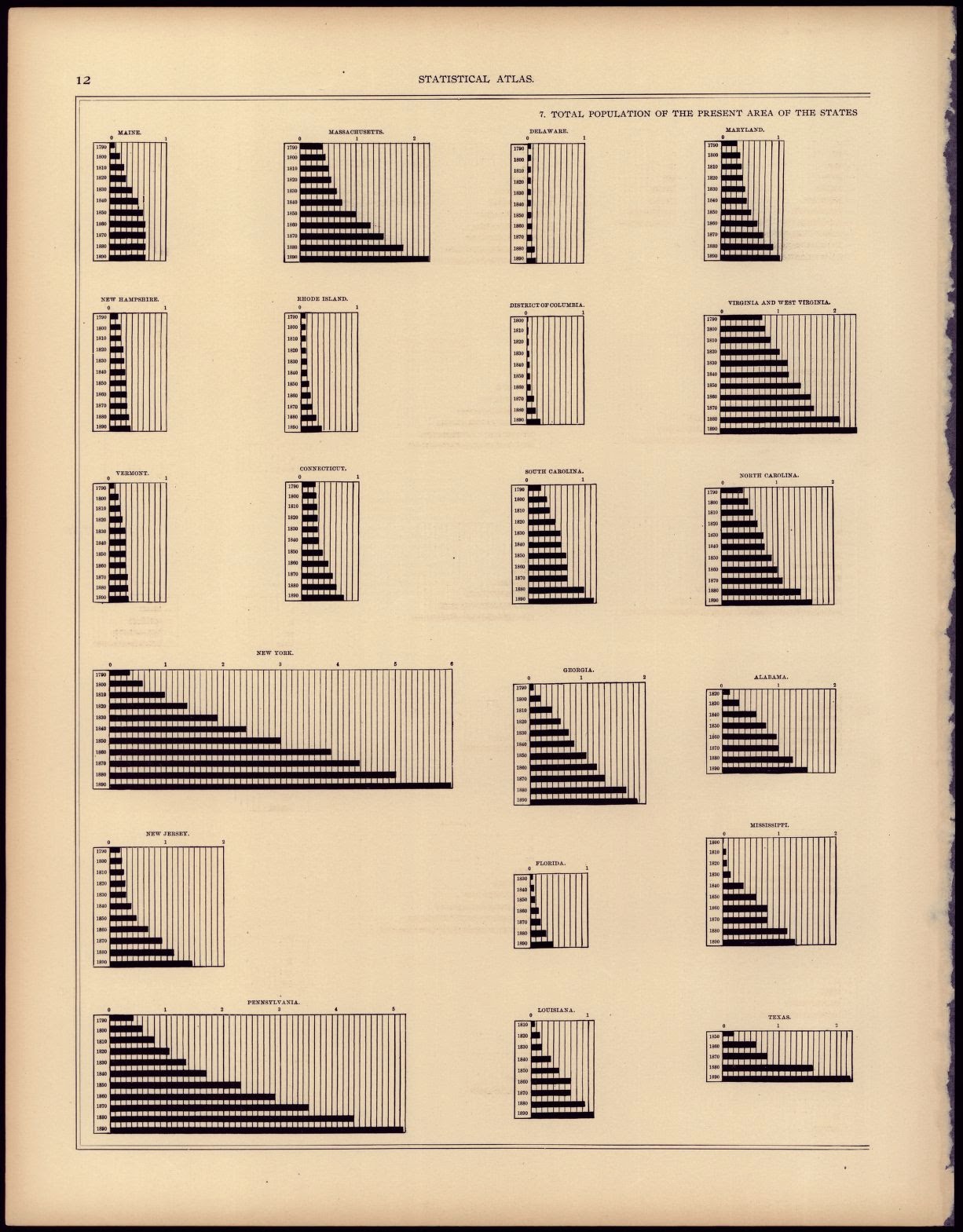

As you may know, the census bureau is probably the single most important organization for inculcating visual-statistical literacy in the American public, particularly through the institution of the Statistical Atlas of the United States published in various forms between 1870 and 1920.

A page from the 1890 Census Atlas: Library of Congress

In 1915, a year after the 1910 census’s atlas was published, the Census bureau circulated a memo to their advisors with a set of proposed rules for graphical presentation. They are a sort of style guide for the Census in particular, but they are obviously transferable to the general case. The famous Strunk and White Manual of Style is based on a set of rules written by William Strunk just three years after this: you could think of this list as a sort of equivalent, except for a field that was nearly new. (You could also think of Edward Tufte, once he finally comes along, as a nice analogue for EB White, unifying elegant and popular sage advice with an occasionally arbitrary set of proscriptions which occasionally give too much ammunition to peevish pedants. But that’s a topic for a different day.)

The first page of the Census rules.

They’re interesting in part simply as good advice: don’t use areas to represent quantities, start the y-axis at zero, etc. My favorite is the advice to avoid any sharp lines at the edges of a graph representing time, because (naturally) “a chart cannot be made to include the beginning or the end of time.” There’s little advice that I’d call bad, although I’d be put off by the command to include all the numbers in a table on paper, if not online. The vocabulary is occasionally odd, but usually easy enough to understand (a line chart is a “curve chart,” for example).

But historically they’re interesting also because of what’s still up for debate. The National Archives hold a copy with comments from a Dr. Hill. (I don’t yet know who that is.Presumably Joseph Adna Hill, as Evan Roberts points out in the comments.). I’ve included Hill’s comments as footnotes, and he manages to disagree with a striking number of what seem like commonsense claims. He believes, for instance, that an X-axis should appear above the chart, not below, because that’s how we read and that’s how numeric tables are read. I’m not sure he’s wrong, or why the under-the-chart form has been so thoroughly triumphant. And I suspect he’s been proven mostly wrong in thinking that color-schemes are not indicators of good or bad objects: “I do not believe, in any event, that the public or any class of the public could educated to associate red with what is undesirable and green with what is desirable.”

Source: Graphic Presentation ; Box 55 ; Series 160 ; Records of the Bureau of the Census, RG-29; National Archives Building, Washington, DC.

The rules (with Dr. Hill’s comments in the footnotes)1

Avoid using areas or volumes when representing quantities. Presentations read from only one dimension are the least likely to be misinterpreted. 2

The general arrangement of a chart should proceed from left to right.3

Figures for the horizontal scale should always be placed at the bottom of a chart. If needed, a scale may be placed at the top also.4

Figures for the vertical scale should always be places at the left of a chart. If needed, a scale may be placed at the right side.5

Whenever possible, include in the chart the numerical data from which the chart was made.6

If numerical data cannot be included in the chart, it is well to show the numerical data in tabular form accompanying the chart.7

All lettering and all figures on a chart should be placed so as to be read from the base or from the right-hand edge of the chart.8

A column of figures relating to dates should be arranged with the earliest date at the top.

Separate columns of figures, with each column relating to a different date, should be arranged to show the column for the earliest date at the left.9

When charts are colored the color green should be used to indicate features which are desirable or which are commended, and red for features which are undesirable or criticized adversely.10

For most charts, and for all curves, the independent variable should be shown in the horizontal direction.11

As a general rule, the horizontal scale for curves should read from left to right and the vertical scale from bottom to top. 12

For curves drawn on arithmetically ruled paper, the vertical scale, whenever possible, should be so selected that the zero line will show on the chart. 13

The zero line of the vertical scale for a curve should be a much broader line than the average co-ordinate lines. 14

If the zero line of the vertical scale cannot be shown at the bottom of a curve chart, the bottom line should be a slightly wavy line indicating that the field has been broken off and does not reach to zero. 15

When curves are drawn on logarithmically ruled paper, the bottom line and the top line of the chart should each be at some power of ten on the vertical scale.16

When the scale of a curve chart refers to percentages, the line at 100 per cent should be a broad line of the same width as a zero line.17

If the horizontal scale for a curve begins at zero, the vertical line at zero (usually the left-hand edge of the field) should be a broad line.18

When the horizontal scale expresses time, the lines at the left and right-hand edges of a curve chart should not be made heavy, since a chart cannot be made to include the beginning or the end of time. 19

When curves are to be printed, do not show any more coordinate lines than necessary for the data and to guide the eye. Lines 1/4 inch apart are sufficient to guide the eye.20

Make curves with much broader lines than the co-ordinate ruling so that the curves may be clearly distinguished from the back-ground.21

Whenever possible have a vertical line of the co-ordinate ruling for each point plotted on a curve so that the vertical lines may show the number of the data observations.22

If there are not too many curves drawn in one field it is desirable to show at the top of the chart the figures representing the value of each point plotted in a curve.23

When figures are given at the top of a chart for each point in a curve, have the figures added if possible to show yearly totals or other totals which may be useful in reading.24

Make the title of a chart as complete and so clear that misinterpretation will be impossible.25

The comments from Dr. Hill

In general I should say that any rules which be agreed upon should not be regarded as rigidly binding. Cases of a kind not considered when the rules were adopted are pretty certain to arise in which it is better to disregard the rule than to observe it↩

I should agree to this. It seems necessary, however, to use areas or volumes when there is a wide disparity between the quantities which are compared, one quantity being very many times greater than another, so that in a comparison by lines or bars, either one bar would have to be very long, extending beyond the limits of any ordinary page, or the other would be so small as to be hardly perceptible.↩

I think I agree to this, if I understand what is meant by it. I should suppose there would be a good many charts to which the rule is not applicable as the arrangement could not be said to proceed in either direction.↩

My preferences would be, in general, to place the figures for the horizontal scale at the top if they are not to be placed at both the top and the bottom. This may be a prejudice on my part but it seems to me more natural and proper to give the designation of a vertical line at the top of the line rather than at the bottom, just as we designate the title of a page, or the heading of a column of figures at the top.↩

I should agree to this.↩

I should agree that this is a good thing to do but would not go so far as to say that it should be done whenever possible. I think it should be done when it can be done simply and conveniently and without introducing too much detail into the chart. In general, the less detail there is on a chart, the more effective it is, and the purpose of a chart, in my opinion, is not so much to convey exact information as to show relationships and tendencies. The great advantage of the chart is that it shows at a glance, relationships which in case of a table or figures could only be discovered after patient study or detailed comparisons. Of course the question of whether to insert figures on the chart or not depends a good deal upon the character of the publication in which it is to appear or the purpose for which it is to be used. If the chart is the only thing that is to be exhibited, or published, it is desirable to have the actual figures inserted if it can be done effectively. In Census publications other than the Statistical Atlas, the chart is usually inserted close to a table presenting the figures on which the chart is based. Under such conditions I do not think it very important the figrues be inserted on the chart.↩

I should agree to this.↩

Not clear about this.↩

These rules [8 and 9] appear to relate to tabular rather than to graphic presentation. The rules here submitted are contrary to the practice of the Bureau of the Census. The Census style, which gives the latest date at the top or left, as the case may be, was introduced in 1870 and has been followed with occasional deviations ever since. This style is likewise followed in most financial reports and is, I believe, not uncommon in other statistical publications. The principal argument in favor of it is that it brings the latest figures, which to the average reader are the most interesting figures, close to the headings in the stub or in the box of the table. The users of the Census reports are accustomed to this method and I believe that more perplexity and annoyance would be occasioned by making the change than by continuing the existing practice.↩

I think the adoption of this rule would be rather foolish. Only a comparatively small proportion of the published charts are in colors. A large proportion of the features presented on charts are neither desirable nor undesirable. In other cases there may be a wide difference of opinion as to whether or not a given feature is desirable or not. It might be said that in such a case the person responsible for the chart should use the color which indicates his own opinion on that question, but I think it would be better to have the chart simply show the facts and leave it to the writer or lecturer to put such interpretation upon these facts as he may deem proper in his text or oral discussion. I do not believe, in any event, that the public or any class of the public could educated to associate red with what is undesirable and green with what is desirable.↩

I should agree to this.↩

I should agree to this.↩

I should agree to this.↩

I should agree to this except that I would substitute “distinctly” for “much”↩

It seems to me that it would be better instead of having a wavy base line to leave the chart without any base line whatever, but with a ragged edge indicated by the broken ends of the vertical lines. I would tear off the bottom of the chart, so to speak, but I would not hem the torn edge.↩

I should agree to this.↩

I should agree to this.↩

Also to this.↩

I think this is probably right.↩

I should agree to this.↩

Also to this.↩

And to this.↩

I am in doubt about this.↩

I should agree to this.↩

Yes, of course, if you can do it; sometimes you can’t.↩

Comments:

Dr Hill is probably Joseph Adna Hill (http://en.wi…

Evan Roberts - Aug 4, 2014

Dr Hill is probably Joseph Adna Hill (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Adna_Hill)

The Wikipedia article is a rip-off of his Census B…

Evan Roberts - Aug 4, 2014

The Wikipedia article is a rip-off of his Census Bureau biography

https://www.census.gov/history/www/census_then_now/notable_alumni/joseph_adna_hill.html

That must be him–thanks! Also pleased to see the…

Ben - Aug 0, 2014

That must be him–thanks!

Also pleased to see the link to the Huntington-Hill method; I ended up reading some congressional testimony about the difficulties in fairly determining the size of congressional districts, and hadn’t gotten around to seeing what we do today.

Unknown - Sep 5, 2014

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

I read the biography I think it applies to today d…

Evan - Oct 4, 2014

I read the biography I think it applies to today data- visualization as well

Regards,

Creately