Just a quick follow-up to my post from last month on using Markdown for writing lectures. The github repository for implementing this strategy is now online.

The goal there was to have one master file for each lecture in a course, and then to have scripts automatically create several things, including a slidedeck and an outline of the lecture (inferred from the headers in the text) to print out for students to follow along in class.

To make this work, I invented my own slightly extended version of the markdown syntax. It has three new conventions:

-

Any phrase in bold is a keyword to be pulled out and included in outlines

-

Anything in a code block is to be used as a slide. Each separate code block is its own slide. Any first-degree header is a full page slide. (The easiest way to do a code block is just to tab indent a line: must of my slides are just a single element line like this:

- As in the previous example, the image format is extended so that labels in slides appear not as alt-text, but in the text above the image: in addition, any image link beginning with the character “>” is treated not as an image but as an iframe, making it easy to embed things like youtube videos or interactive Bookworm charts.

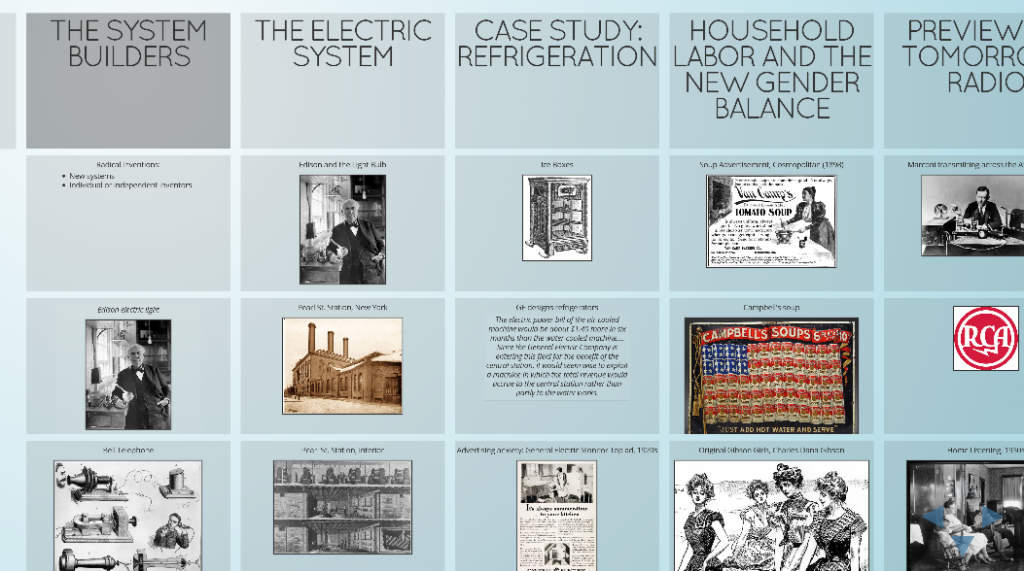

The slide decks are built with reveal.js, which drops everything into a nicely organized batch. Here’s what one looks like. (This is for a lecture on household technologies in the 20s). My favorite feature is that by hitting escape, you get an overall view of everything in the lecture sorted by header–this is particularly useful when studying for exams, because those headers align exactly with the outlines.

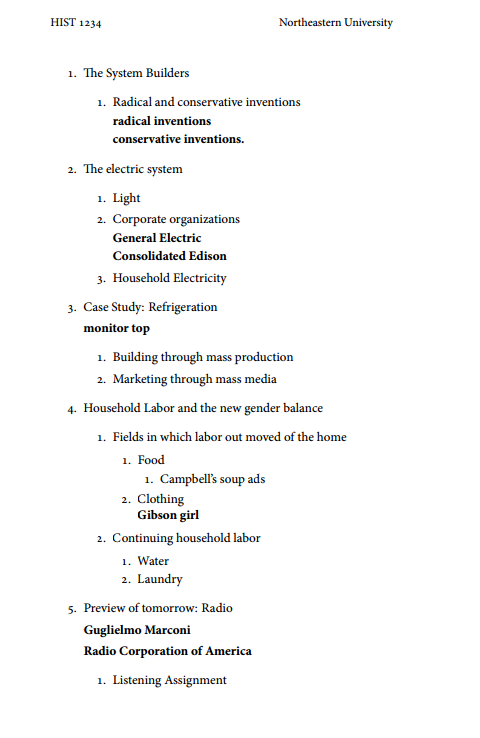

The outlines are produced from the same lecture notes, but in a different way; rather than pull the code blocks, they walk through all the headers in the document and append them (and any bolded terms) to a new document that students can see. For that lecture, it looks like this:

There are a few things I still don’t love about this: image positioning and sizing is not so good as it is in powerpoint. But the thing that’s nice is that it’s extremely portable; if I don’t make through the end of a lecture, I can just cut out the last few paragraphs, paste them into the next day’s document, and have the outline and slides immediately reflect the switch for both days. This makes a lot of last-minute, before-class changes dramatically easier.

The basic scripts, though not the full course management repo, is up on github.The code is in Haskell, which I’ve never written in before, so I’d love a second set of eyes on it. Some brief reflections on coding for pandoc in Python and Haskell follow.

I thought it would be easy to switch between headers and an outline, but they turn out to have almost nothing in common in the Pandoc type definition; the outline needs to be built up recursively out of component parts. It’s an operation that’s much closer to really basic data structures than anything I’ve done before.

I initially used the pandocfilters Python package for this. That code is here. It basically works–thanks primarily to insight gleaned from an exchange on GitHub between, I think, Caleb McDaniel and John McFarlane that I’ve lost the link for) that you need to scope a global python variable and append to it from a `walk` function. But it has a tendency to break unexpectedly, and uses an incredibly confusing welter of accessors into the rather ugly pandoc json format. Plus, it’s fundamentally an attempt to write Haskell-esque code in Python, which is about the least pleasant thing I’ve ever seen.

By the time I made that python script work. I had spent a couple hours reading and re-reading the pandoc types definition, and it seemed like it would simpler to just write the filter in Haskell directly. (I did a few Haskell problem sets for a U Penn course this summer out of curiosity; without that basic understanding of Haskell data types, I doubt I would have been able to understand the Pandoc documentation.) The lecture-to-outline Haskell code, to my surprise, ended up being a bit longer than the Python version (though much of that is type definitions and comments, which doesn’t really count). If anyone out there who knows Haskell can explain to me a better way to avoid some of the stranger elements in there (particularly the reversing and unreversing of lists just to allow pattern matching on them, which is a substantial proportion of what I wrote), I’m all ears.

Programming in Haskell is certainly more interesting than python; I agree with Andrew Goldstone’s comment that “whereas programming normally feels like playing with Legos, programming in Haskell feels more like trying to do a math problem set, with ghc in the role of problem-set grader”. I’m left with a strong temptation to write a TEI-to-Bookworm parser, which I’ve previously sketched in Python, in Haskell instead; both for performance and readability reasons, I think it might work quite well. Stay tuned.